The council is committed to making Scouting accessible and enjoyable to all Scouts, regardless of their abilities.

The basic premise of Scouting for youth with disabilities is full participation. Youth with disabilities can be treated and respected like every other member of their unit. They want to participate like other youth - and Scouting provides that opportunity.

Essentials in Serving Scouts with Disabilities

The BSA's policy is to treat members with disabilities as much like other members as possible. It has been traditional, however, to make some accommodations in advancement if absolutely necessary. By adapting the environment and/or our instruction methods, most Scouts with disabilities can be successful in Scouting.

Unit leaders can make accommodations for timing, scheduling, setting, presentation, and response when helping a Scout with their advancement.

Adaptive Options and Ideas for Assisting Scouts with Disabilities

Adaptive Options and Ideas for Assisting Scouts with Disabilities

Source: Essentials in Serving Scouts With Disabilities Handout available at www.scouting.org/disabilitiesawareness.aspx.

Accessibility

Ensure routes are easily accessible for all. One can find trails using internet searches for “wheelchair accessible trails.” Most state parks maintain lists of accessible trails. The Rails to Trails Conservancy has a searchable web page with many accessible trails. You can also find a list on the Working with Scouts with disAbilities website at wwswd.org.

Time and Place

Many challenges can be addressed simply by adjusting the setting of the activity to be less distracting, allowing more time or more frequent breaks, or switching the teaching method between tactile, visual, and auditory approaches.

Here are some other ideas to think about:

Materials Adaptations

Example: A Cub Scout has little hand strength and is trying to carve.

Solution: Substitute a bar of soap or balsa wood.

Example: Boy Scout has poor fine motor skills and is learning knots.

Solution: Use thick, flexible, braided rope.

Architectural Adaptation

Example: A Scout in a wheelchair is unable to go hiking because the trail is inaccessible.

Solution: Substitute “trip” for “hike” or select alternative route.

Leisure Companion (Buddy) Adaptation

Example: A Cub Scout cannot stay on task and runs around.

Solution: An adult or older youth can become a buddy for the Cub Scout.

Cooperative Group Adaptation

Example: A Cub Scout has difficulty remembering the steps in a project.

Solution: Work in cooperative groups to ensure completion for everyone.

Environmental Adaptations

Example: The meeting area is in an area with bright lights or florescent lights.

Solution: Try dimming the lights or provide sunglasses.

Example: The meeting room walls are cluttered with memorabilia.

Solution: Relocate the stuff to clear the wall that the group faces.

Example: The meeting room is loud with chattering Scouts.

Solution: Move the activity outdoors where voices can carry.

Appropriate Peer and Adult Supports

Appropriate Peer and Adult Supports

Source: Essentials in Serving Scouts With Disabilities Handout available at www.scouting.org/disabilitiesawareness.aspx.

Parents as partners

Our goal is to work with parents to promote independence. Do not let the need for a parent at meetings or outings to become a crutch in dealing with the Scout. This may appear to convey the impression that instead of addressing the concern, you want the parent to handle it. There may be times when a parent or caregiver needs to attend meetings and outings. This will need to be addressed on an individual basis. It will be important to watch this process closely to avoid hindering the Scouts development of independence.

Examples of appropriate supports from parents or caregivers:

- Signing (ASL), assistance with communication devices, food allergies, personal care assistance (hygiene), making suggestions for accommodations or adaptations.

Parent or caregiver support is NOT:

- Doing things a peer can do, like pushing a wheelchair, being a buddy, transcribing, or doing things youth can do independently if given enough time or adaptations, etc

Peers as partners

At the leader’s discretion, Scouts may earn credit for leadership positions when being a peer buddy. Peer buddies should attend PLC meetings with other Scouts in leadership positions. Their role is to help facilitate or anticipate things for their buddies during PLC. For example, if a youth with disabilities is a current patrol leader, but has a significant writing disability, the peer can take meeting notes for them.

Units may find it helpful if designated peer buddies first have earned the Disability Awareness merit badge. Otherwise, a short training or orientation can be held to set the expectations and parameters for the program. An agenda might resemble this:

Sample Peer Buddy Training Agenda

I. Overview

a. Purpose of peer buddies program

b. What is inclusion? What is it not?

c. Discussion of individual roles for peers, Scouts with disabilities, parents, and leaders across various Scouting settings.

II. Expectations

a. Learn about “ability awareness”

b. Roles: friendship, help develop independence, be helpful only when needed.

c. Provide models

d. Attitude: encouraging, positive, and accepting

e. Confidentiality (privacy)

f. Behaviors

g. How to act and react

III. Peer Relationships

a. Appropriate friendships

b. “Hanging out” with peers

d. Inappropriate relationships

e. Advocacy to rest of Scouting unit and society at large

How to Have a Joining Conference with a New Family

How to Have a Joining Conference with a New Family

Source: Essentials in Serving Scouts With Disabilities Handout available at www.scouting.org/disabilitiesawareness.aspx.

What - A joining conference is a lot like a parent-teacher conference at the beginning of a school year. The den leader should have a joining meeting for every Scout. About 15% of Scouts have an acknowledged disability1 and most disabilities don’t change one’s appearance, so “you can’t judge a book by its cover.” Keep the tone of the conference relaxed and friendly.

Why - A joining conference builds trust and rapport with the parents as partners in delivering the Scouting program. It provides useful information about the unique attributes of the youth that will help you play to each youth’s strengths, provide for each youth’s special needs, and prevent conflict between the members of your unit.

When - A joining conference should take place soon (first month?) after a youth joins the unit. Remember, Scouting is open to all youth, so the conference happens after the youth has been accepted. It is not a “job interview”. The youth has nothing to prove before joining the unit.

Attendees - One or both of the youth’s parents and preferably at least one responsible, disability awareness trained leaders who will have direct contact with the youth should attend. In Cub Scouting, the den leader should be included. In troops, crews and ships, the youth is often included in the meeting, but common sense should prevail when deciding whether or not to include them.

Where - This is a candid and private conversation with the family, so the meeting should be out- of-earshot of others. It is OK to do this at a regular unit meeting, but you might have to hold the conference at a different place or time in order ensure privacy.

Confidentiality - Parents decide what leaders may know. Assume confidentiality until the parent gives permission to share with others. If one believes the youth will benefit from other key adult and youth leaders being brought into the loop, one may ask permission to brief them.

Topics - During the joining conference you want to learn:

- What are unique strengths and struggles?

- What accommodations/adaptations are being made at home and at school?

- Does anything trigger emotional or behavioral struggles?

- How does he/she act when situations are about to be overwhelming?

- What concerns do the parents have about putting their child in Scouting?

– Never press for a diagnosis. Practically speaking, you don’t need to know what the condition is called as long as you know what to watch out for and what to do.

A Sample Script – Hi. I’m name and I’m the leader position of unit type ###. I’m glad you and youth name have joined our unit. The other leaders and I want to give your child the best experience possible. I know we have told you what our unit is like, and it will help if you can tell us what makes your child unique. Can we have a few minutes? To start with, is there anything you are concerned about? What are their strengths? Is anything harder for your child than for others? Is there anything that helps the youth be successful at home or at school? Is thereanything I need to watch out for or avoid doing with your child? Is there anything your son or daughter needs me to do? When he or she is struggling, how can we best help your child?

1 The numbers are almost certainly higher as many moderate disabilities are not formally diagnosed by professionals and others are kept secret by the family.

1 The numbers are almost certainly higher as many moderate disabilities are not formally diagnosed by professionals and others are kept secret by the family.

Planning Successful Outings for Scouts with Disabilities

Planning Successful Outings for Scouts with Disabilities

Source: Essentials in Serving Scouts With Disabilities Handout available at www.scouting.org/disabilitiesawareness.aspx.

All youth should explore their limits and learn that some are more difficult than they imagined. Leaders new to working with Scouts who have disabilities must prepare for unexpected situations and have contingency plans to minimize the level of risk. For example, he should ensure a Scout with a mobility limitation attends outings in areas with accessible facilities. Scouts with invisible disabilities like those with severe allergies or experience anxiety or panic attacks can be challenging to plan. A leader’s contingency plan may include Plans B, C, or D.

- Expect the Unexpected – Weather changes unexpectedly. A Scout gets ill midway. Routes are harder than the map indicates. The point: planning for contingencies is important for all Scout outings, with or without Scouts with disabilities.

- Ability Levels – When planning outings to challenge Scouts of varying ages and skills, it makes sense to divide Scouts into groups of similar ability levels, provided one has enough leaders to monitor the groups’ safety. The Scouts with disabilities group obviously should have the least challenging yet reachable types of activities according to each Scout’s abilities. It is important not to isolate Scouts with disabilities from other Scouts. Even if caregivers must accompany a Scout, at least two other youth should go along too. Consider these examples:

- Canoeing – Start the advanced level paddlers at a drop-off point upstream of the beginners and then have them all rendezvous at the pull-out point. A mobility restricted youth rides with others paddling. (Cycling is similar)

- Rock Climbing – Give beginners more instructions and have them boulder before attempting roped-up climbing. A youth with limited strength should climb with rope tension assistance. (Note: zip lining is exciting and accessible for Scouts.)

- Hiking – Find two routes between the start and finish points, with the advanced group going further with more elevation change. The easier route should be wheel chair accessible. (Cross-country skiing is similar)

- Figure Eight Routes – Plan on making a Figure Eight route with the base camp, start, and finish points in the middle of the loop. That way, it’s easier for participants opting out of the second half of the route or dropping off gear at the mid-point to allow successful completion.

- Bail-out Points – Consider a stopping point of your planned route if the need arises. This becomes important in dealing with both injuries and disabilities. On a water route, identify the locations of vehicle accessible points such as bridges and riverfront houses. On land routes, identify the trail shortcuts, crossings, those closest to roads, trail heads, and parking areas along the way.

- Communication and Support Vehicles – Determine how members can send a message to a designated leader or group at a rendezvous point if they cannot finish the route and need to be picked up. On longer routes, designate a leader to drive ahead to identify the bail-out points through the day for those needing assistance.

Conversation Starters

Conversation Starters

Source: Essentials in Serving Scouts With Disabilities Handout available at www.scouting.org/disabilitiesawareness.aspx.

Asking these questions will enable open communication with the Scout and their family.

Communication Hints:

- Remember to follow Youth Protection guidelines while being respectful of trust, confidentiality, and privacy.

- If one needs to talk to a parent or youth about a specific situation, avoid blaming the person which may put the youth on the defensive. Help them understand their best interest is at heart. For example ask the parent, “We are having difficulty managing your child’s (specific behavior), and we want to make sure he or she is experiencing all that Scouting has to offer. What do you suggest we do to get a better handle when your child displays this type of behavior?”

- Focus on fostering Scout-like behavior. A leader should not suggest in any way either through tone of voice or body language he or she thinks the Scout has character flaw or their caregiver lacks parenting skills. Be mindful the parent knows their child best.

- Involve the Scout in problem solving discussions. The more one includes the Scout in the process, the more the Scout takes ownership in their experience. Encourage all Scouts to ask for help or speak up if they don't understand something. Some Scouts may need to approach a leader individually asking to advocate for them.

- Ask follow up questions probing for more details and clarity: “Why?”, “How?” “Tell me more …” etc. Keep voice calm, with a positive demeanor, and one’s emotions neutral.

Sample Conversation Starters:

- What is the best way for me to (support, encourage, help) you?

- What roles make you feel most successful?

- If we could just drop what we’re doing to do something fun, what would it be?

- What do you think makes a great Scouting unit?

- Describe the perfect outing.

- What can Scouting do for you? What are your goals for this year? Next year, and so on?

- Which of our pack (or troop) activities did you enjoy most last year? Which did you enjoy the least? What made them enjoyable or difficult? How can we improve those activities or make them more inclusive?

- What were some expectations you had of our pack (or troop) that we didn’t meet?

- What can our leaders do to improve communication, program planning, or awareness?

- Would you be willing to help us improve these areas?

Self-Removals and Slowing Down Activities:

- Self-removal is a good tactic to use when a Scout is feeling too overwhelmed, building up anger, or just needs to pull themself together.

- Self-removal needs to be Scout initiated. Have a designated isolation area like a tent set up at camp with coping tools like a book or playing cards to help settle them down.

- Ask a leader to give a visual cue both he and the Scout agree upon such as holding up four fingers or placing one’s hand on the left side of the chest. This minimizes the self- removed Scout feeling singled-out without other Scouts knowing what you are doing.

- Use an agreed-upon sound such as a mobile device ring tone, clicker, bell, or, cue.

How to slow down activities:

- Give a verbal warning such as: “You have five minutes left!” then repeat at two minutes, and again at thirty seconds. Give a visual cue for time remaining.

- Give a noise warning with a whistle or bell.

- When one sees an activity getting out of control, stop all action before it escalates. For example, tell Scouts they need a water break or two-minute recess before resuming.

- If Scouts need to quite down quickly, tell them to breathe through their noses. This makes them close their mouths, and affords leaders time to think about the next step.

A Scout with Autism – Where to Start?

A Scout with Autism – Where to Start?

Source: Abilities Digest Vol. 2, No. 2 (Spring 2015)

One in every 42 boys has Autism, a developmental disability. It isn’t diagnosed until most youth reach grade school and even then, common neurobiological disorders like ADHD/ADD may be diagnosed first. Thus, an ever increasing number of units have at least one Scout on the Autism spectrum. so leaders should get to know the family, too.

Step One: The Scout’s family fills out an Individual Scout Profile.

The Individual Scout Profile (ISP) is a worksheet developed by Autism Empowerment and the Autism and Scouting program to help leaders learn each Scout’s strengths, challenges, and learning style. Some leaders ask all Scout families to fill out the ISP as it provides clues to potential sensory challenges and attention needed to medical, health, and safety issues that will ensure a good experience for each Scout in the unit. The ISP is accessible at www.autismempowerment.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/ISP.pdf.

Step Two: The Parents or Caregiver and Unit Leader Meet

Once the Scout with autism joins Scouting, the unit leader should arrange a meeting with the parents or caregiver to get to know the family, and discuss their son’s completed ISP form. Parents are experts on their son’s autism.

The initial discussion prepares the leader for any sensory or learning challenges he needs to be aware of, and think about ways to help the Scout regardless of their diagnosis. By establishing a positive connection with the Scout’s family, leaders show they care and want the Scout to succeed. Leaders and parents should have this goal in mind. Preface the meeting by letting them know you are interested in helping their child have a positive experience, not keeping them out of Scouting. Follow the Five Ps in addition to the motto “Be Prepared:”

- Be Polite

- Be Professional

- Be Positive

- Be Patient

- Be Proactive

A short meeting to go over forms and “get to know you” keeps the initial discussion time reasonable but still allows bonds to form. In reality, what you will be discussing may need to take longer but be mindful of the time so no-one is overwhelmed. During the meeting, here are some of the things you will learn:

- Find out what accommodations the Scout may need if applicable.

- Find out what sensory, emotional, social, dietary restrictions, or allergy challenges may be checked, making sure you verbally clarify each area.

- Find out if the Scout has sensory issues or emotional triggers as these may cause meltdowns or shutdowns.

- Listen non-judgmentally. Families do not want to be pitied or be made to feel that their child is going to be a burden.

- Ask what level of privacy the family prefers.

The leader meets with the Scout following the discussion with their parents or caregiver.

Privacy

The family should indicate what information about the Scout’s condition should be disclosed to others in the troop. This should be discussed without the youth. If a family is very open about disclosure this is an opportunity to offer them the chance to make a presentation to other leaders and/or Scouts about what autism may look like for their Scout son. When in doubt, it is better to follow the family's lead. For more information, see the Autism and Scouting Leadership Training Kit from Autism Empowerment, available for free download at www.AutismandScouting.org.

Autism and Scouting Autism Empowerment

Accept, Enrich, Inspire, Empower Scout Leader tips for helping Scouts on the Spectrum

Source: Three Fires Council

1. Get to know the Scout and their family!

2. When you meet one Scout with Autism, you’ve met ONE Scout with Autism.

3. Find out what, if anything may cause a meltdown/shutdown.

4. Find out what works best to help the Scout recover from a meltdown or shutdown.

5. Find out any sensory issues the Scout might have.

6. Find out how the Scout learns best.

7. Find out any special interests that the Scout has.

8. Incorporate these special interests to help the Scout learn.

9. Have a place for the Scout to go for sensory breaks.

10. Allow for transition time and processing time.

11. Use positive encouragement to help in taking part in activities.

12. Explain the reason why something is being done.

13. Be careful of using sarcasm either directly or around the Scout.

14. Don’t talk down to the Scout and make sure to monitor your tone.

15. Live by example, Live the Scout Law and Oath – Integrity matters.

16. Try to help the Scout achieve success while having fun along the way.

17. Always follow the guide to safe Scouting.

18. Always remember to respect the family’s and Scout’s privacy.

19. Accept the Scouts for who they are, where they are.

20. Enrich the Scout’s life by teaching lifelong skills.

21. Inspire the Scout to be exceptional. Chances are that he/she will inspire you too.

22. Empower the Scout by giving the tools to be self-sufficient and successful.

For more information visit:

Preparing for Summer Camp

Preparing for Summer Camp

Source: Abilities Digest Vol. 2, No. 2 (Spring 2015)

Summertime means summer camp for most Scouts. They want to take part in the activities and, most importantly, have fun. This takes preparation, especially for new Scouts and those with disabilities. The unit leader should take time to think about each Scout as an individual and how they will react to camp routine, especially for those who have not attended camp before. Start by identifying roadblocks— camping features that prevent Scouts from participating or feeling comfortable. Make sure a leader watches for those roadblocks and is ready to bring the challenge within reach of the Scout’s abilities.

Summertime means summer camp for most Scouts. They want to take part in the activities and, most importantly, have fun. This takes preparation, especially for new Scouts and those with disabilities. The unit leader should take time to think about each Scout as an individual and how they will react to camp routine, especially for those who have not attended camp before. Start by identifying roadblocks— camping features that prevent Scouts from participating or feeling comfortable. Make sure a leader watches for those roadblocks and is ready to bring the challenge within reach of the Scout’s abilities.

Involve the Scout’s parents in the planning process. Invite them to attend camp with the unit if appropriate. All campers should have buddies, but those with special needs should have a buddy who understands their disabilities and can help with roadblocks.

If Scouts have anxieties about unfamiliar places, make the camp familiar ahead of time. One Venturing crew produced a videotape of the campsite which helped smooth the transition from home to camp. In another case, Scouts actually visited the camp ahead of time and saw their assigned campsite, trails, and activities centers.

Mobility poses a challenge, especially on camp trails. Use a camp map and pay attention to travel needs when planning a camper’s activities. Scouts with Down syndrome, for example, have low muscle tone. They tire easily from walking back and forth to the campsite. After lunch, instead of having them walk to the campsite to rest for an hour, they should just hang out in the dining hall with their buddies to wait for afternoon activities. Campers with wheelchairs should be familiar with camp trail conditions. The unit should plan to bring a set of tools to maintain wheelchairs or other mobility equipment. Bolts often shake loose after maneuvering on bumpy trails.

Camp staff are another resource. Contact them ahead of time about each camper’s special needs or restrictions. The staff may have suggestions for appropriate activities or alternatives to ones the camper should avoid. A bit of forewarning also lets staff and counselors make adjustments whenever possible. Not all camp directors can adapt their programs, but all strive to give campers a fun and rewarding experience.

When arriving at camp, leaders should identify “cool zones” in each activity area. This is a quiet place campers can retrieve to when feeling overwhelmed, over-stimulated, fed-up, etc. This is good for any Scout, not just Scouts with disabilities. Caring leaders realize everyone needs a break to gather themselves. “Cool zones” should be within the responsible leader’s view. Planning and preparation can make summer camp fun for everyone.

Creativity - The Key to Alternative Requirements

Creativity - The Key to Alternative Requirements

Leaders are often challenged to come up with an alternative requirement that’s challenging to a Scout with special needs.

Leaders are often challenged to come up with an alternative requirement that’s challenging to a Scout with special needs.

Consider a common concern heard from many parents: ”My son has a disability and cannot complete the swimmer rescue requirement 9c for the First Class rank: “With a helper and a practice victim, show a line rescue both as tender and as rescuer. (The practice victim should be approximately 30 feet from shore in deep water.)”

In general, the following suggests an example of an alternative to the rank requirement proposed and approved by a council advancement committee: A Scout was confined to an electric wheelchair with no use of their legs and little use of their hands, but did have a service dog. The rescue was performed in a rectangular swimming pool. His service dog first set the end of the throw ring line in the Scout’s lap where he could grab it with his hand. The Scout then moved his wheelchair around the pool while holding onto the line; the throw ring was pulled along 20 ft. or so behind the wheelchair. Once the Scout turned to go around the other side of the pool, the line fell into the water, and as the Scout continued to circle around the pool, the throw ring was pulled into and across the pool until it came within reach of the practice victim.

This example was not the only solution, but it met the Scout’s special circumstances.

Leaders should try to be creative in their thinking, whatever the Scout’s situation, special needs or otherwise. Remember, it is the responsibility of unit leaders to help youth succeed, not to put up unnecessary roadblocks.

Teaching Knots to Scouts with Poor Fine Motor Skills

Teaching Knots to Scouts with Poor Fine Motor Skills

Source: Three Fires Council

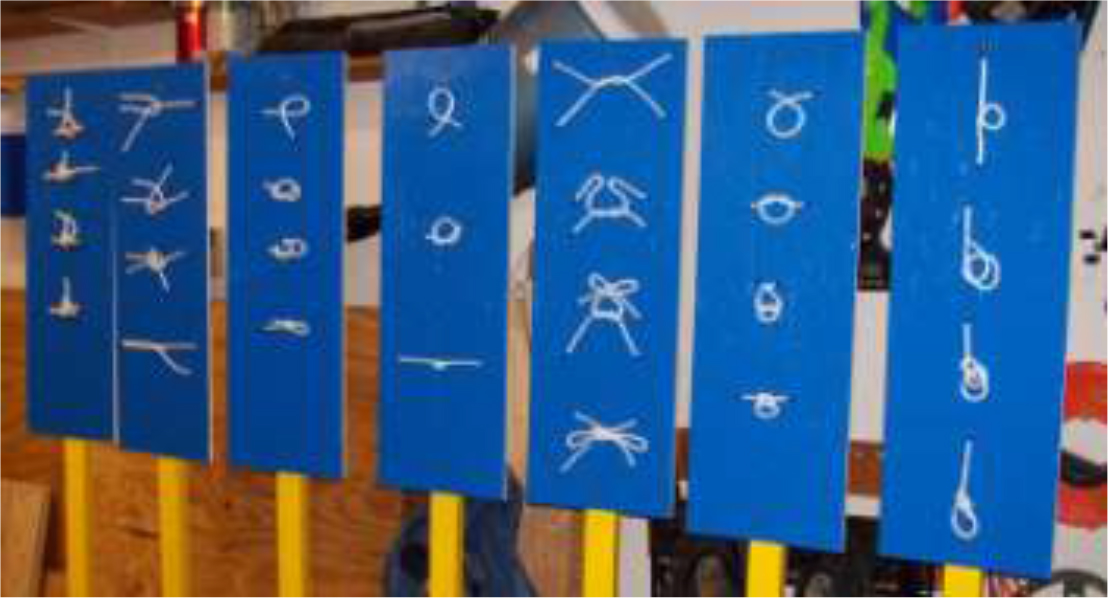

From its inception, Boy Scouts of America has provided a program designed to be inclusive for youth of all abilities; however advancing in rank can be especially challenging to those with poor motor skills due to the knot tying requirements for Scout through First Class. This handout offers tips and helpful hints for leaders working with Scouts who posses poor fine motor skills. Keep in mind that all scouts learn in different ways. What works for some may not work for others and you may have to experiment with a number of methods to achieve success.

From its inception, Boy Scouts of America has provided a program designed to be inclusive for youth of all abilities; however advancing in rank can be especially challenging to those with poor motor skills due to the knot tying requirements for Scout through First Class. This handout offers tips and helpful hints for leaders working with Scouts who posses poor fine motor skills. Keep in mind that all scouts learn in different ways. What works for some may not work for others and you may have to experiment with a number of methods to achieve success.

Tips for teaching knots to Scouts with poor fine motor skills

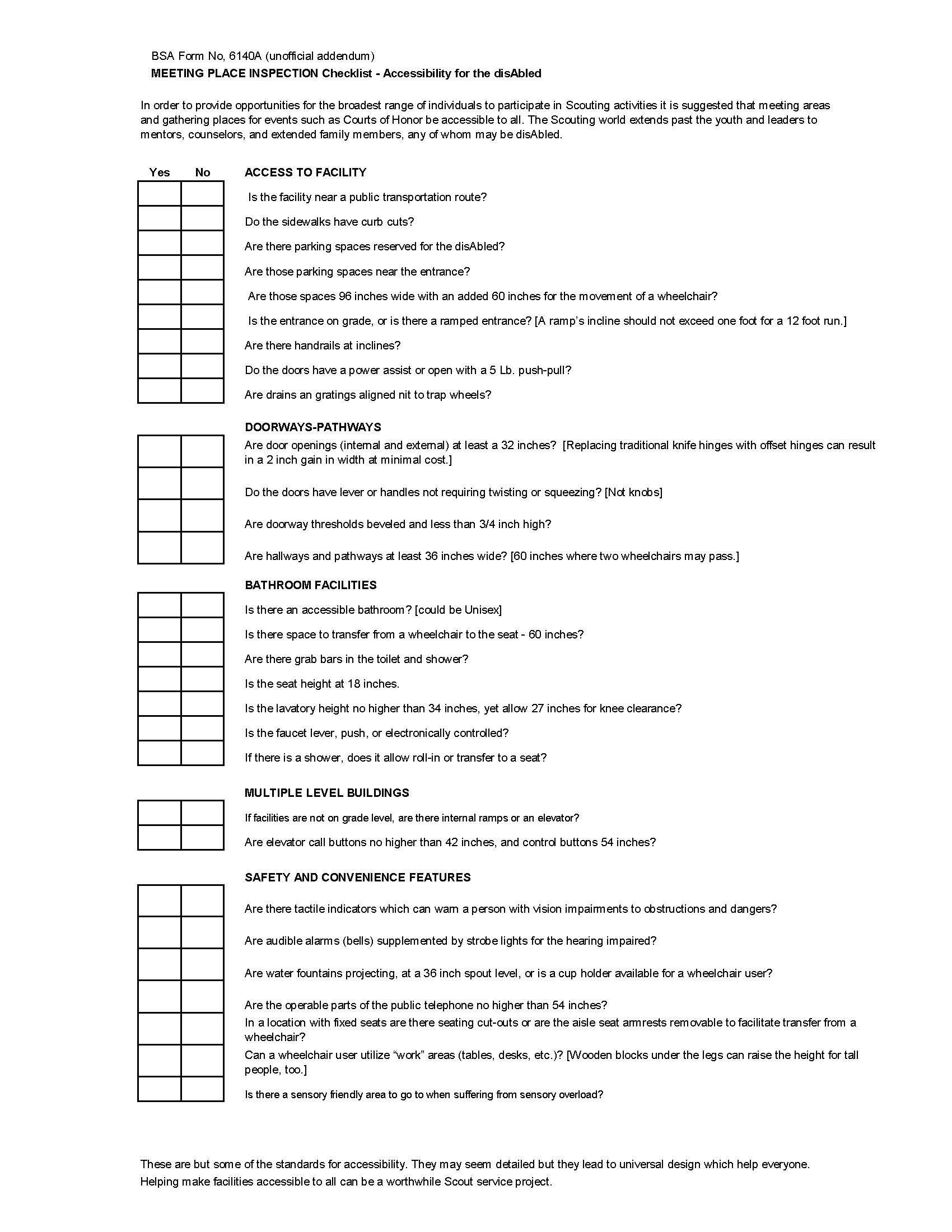

Meeting Place Inspection Checklist Accessibility for the disAbled

Meeting Place Inspection Checklist - Accessibility for the disAbled

Source: Three Fires Council

In order to provide opportunities for the broadest range of individuals to participate in Scouting activities it is suggested that meeting areas and gathering places for events such as Courts of Honor be accessible to all. The Scouting world extends past the youth and leaders to mentors, counselors, and extended family members, any of whom may be disAbled.

Youth with ADHD: Useful Tips for Scout Parents

Youth with ADHD: Useful Tips for Scout Parents

Source: Advancement News Vol 6. No 2

Source: Advancement News Vol 6. No 2

The mission of the Boy Scouts of America — “to prepare young people to make ethical and moral choices over their lifetimes by instilling in them the values of the Scout Oath and Law”—has provided a structure, challenge, and an outdoor physical focus that have helped youth succeed. For that reason, Scouting has long been a great program for youth who have Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, or ADHD, and for many, their successes have not just been while they are Scouts, but have continued throughout their lives.

The BSA’s National Disabilities Awareness Task Force provides some tips to share with parents of Scouts with ADHD:

- If your Scout has ADHD, let your Scout leader know. Tell the leader what works well and what does not help.

- If your Scout takes medication to help them focus at school, it may also help them focus better during Scout activities. You may want to discuss this issue with your Scout’s physician.

- Make sure your Scout knows that his medication is meant to help them focus, not to make them behave or be good.

- Be sure to tell the Scout leader what your son’s needs are, whether he is going on a day trip, a weekend camping trip, or a week at summer camp. There are many things the leader can do to help your Scout be successful and have fun—if he or she is informed.

- Consider getting trained to be a Scout leader yourself.

Note: Medications are a serious concern for Scout leaders. The following guidance is provided from Guide to Safe Scouting: “Prescription medication is the responsibility of the individual taking the medication and/or that individual’s parent or guardian. A leader, after obtaining all necessary information, can agree to accept the responsibility of making sure a Scout takes the necessary medication at the appropriate time, but the BSA does not mandate or necessarily encourage the leader to do so.” Also, “if state laws are more limiting, they must be followed.”

Tips for Scout Leaders of Youth with ADHD

The National Disabilities Awareness Task Force further provides some tips for Scout leaders:

- Try to let the Scout who has ADHD know ahead of time what is expected. When activities are long or complicated, it may help to write down a list of smaller steps.

- Repeat directions one-on-one when necessary, or assign a more mature buddy to help them get organized.

- Compliment the Scout whenever you find a genuine opportunity.

- Provide frequent breaks and opportunities for Scouts to move around actively but purposefully. It is NOT helpful to keep Scouts with ADHD so active that they are exhausted, however.

- When you must redirect a Scout, do so in private, in a calm voice, unless safety is at risk

- Whenever possible, sandwich correction between two positive comments.

- Be aware of early warning signs, such as fidgety behavior, that may indicate the Scout is losing impulse control. When this happens, try a private, nonverbal signal or proximity control (move close to the Scout) to alert them that they need to focus.

- During active games and transition times, be aware when a Scout is starting to become more impulsive or aggressive.

- Expect the Scout with ADHD to follow the same rules as other Scouts. ADHD is NOT an excuse for uncontrolled behavior.

- Offer feedback and redirection in a way that is respectful and that does not embarrass the Scout. When Scouts are treated with respect, they are more likely to respect the authority of the Scout leader.

- Keep cool! Don’t take challenges personally. Scouts with ADHD want to be successful, but they need support, positive feedback, and clear limits.

- Find out about medical needs. Make sure you have what your council requires to ensure the Scout’s medical needs can be met, or have the parent come along.

- Offer opportunities for purposeful movement, such as leading cheers, performing in skits, assisting with demonstrations, or teaching outdoor skills to younger Scouts. This may improve focus, increase self-confidence, and benefit the pack or troop as a whole

- Scouts with ADHD are generally energetic, enthusiastic, and bright. Many have unique talents as well. Help them use their strengths to become leaders in your troop.

Every unit is different, and every Scout with special needs has a uniqueness all his or her own. If a problem arises, parents and adult leaders can usually handle it themselves; however, knowledgeable Scouters may offer additional solutions and valuable perspectives. The council Disabilities Awareness Committee is available to provide training and to be a resource to help resolve challenges.